Henry Owens, Volunteering - Capture

1939 - 1940

These accounts are in Henry Owens' own words, compiled by his son, Robert Owens, in November 2001.

The Experiences of Prisoner of War No. 14704

Henry Owens – Gunner Artificer, RA

"My Dear Sister Rene,

I was delighted to receive last week two letters from you dated Nov 18th. Your letter recalls to me our childhood days, you were my big sister, and I believe you understand me more than anyone else in the family. Times have changed, years have passed, I have seen at least six continental countries since we last met. We had a hard time of it in France, both in the Maginot and on the Somme, but the unshakable confidence you and the rest of the family placed in me undoubtedly helped me when things seemed hopeless." - Henry Owens

I was born in Collingwood Street, Birkenhead, on 30th September 1917, five months after my father James had been killed in action in the First World War, whilst serving with the Australian forces in France. My mother was left a widow at 25, with three boys and two girls to look after. Times were hard in the aftermath of the Great War, although she did receive a War Pension from the Australian government.

When I was about five years old, my mother met and married William (Billy) Neville. They had two daughters. He was a splendid father to his daughters, and stepfather to us. Tragically, he was killed as a result of the Blitz in 1940. I was educated at Woodlands Infant School, and later at Conway Street Central School, which I left at the age of fourteen to take a job as an errand boy with a firm of weighing machine engineers. At the age of 16 I went across the Mersey to Liverpool, where I began my apprenticeship.

Henry Owens at Le Havre

show infoDescription:

Gunner Henry Owens (top left), Le Havre, 1940

Credit:

Thanks to Robert Owens (son of Henry Owens)

Tags:

War clouds were looming, and in June 1939 I joined the Territorial Army 289 Battery, 38 Regiment Heavy Anti-Aircraft Royal Artillery, based at Chetwynd Drill Hall Bidston, as an artificer (gun fitter). On August 24th 1939 we were re-mustered and sent to a designated gun site at Sutton Weaver in Cheshire. The site was a clover field. We had to cut the grass, erect huts, lay on our own water and electricity supply, position and camouflage the guns, and sandbag - all at breakneck speed. It was damned hard work, but we enjoyed it, and we were ready, when war was declared on September 3rd, to give Hitler a “bloody nose”.

During the period of the “Phoney War” we perfected our gun drill, and were sent to a firing range at Ty-Croes in North Wales for actual gun firing - at a “sleeve” towed by a plane. We always worried we would hit the plane instead. Early in January 1940 I was called to the adjutant‟s office, where I was told I was to be posted to the 51st Anti-Tank Regiment, 201 Battery, 51st Division based at Bordon in Hampshire, as they were short of gun fitters.

When I finally arrived, having been delayed by deep snow, I was informed that I would be in the advance party, leaving tomorrow morning for “somewhere”. I assumed this meant France, and so it turned out. We landed at Le Havre.

After loading our guns onto flatbed railway trucks, we were transported to Armentières near the Belgian frontier, where we were deployed along the front for approximately three months. We then received a change of orders, and were sent to Alsace Lorraine and deployed on the no man‟s land between the Maginot Line and the German front line.

When the Germans attacked, they bypassed the heavily fortified Maginot Line. Once they had overrun Holland and Belgium, the 51st Division was left dangerously exposed. We had to carry out a fighting retreat to try and link up with the rest of the British forces, who were, in turn, retreating to Dunkirk.

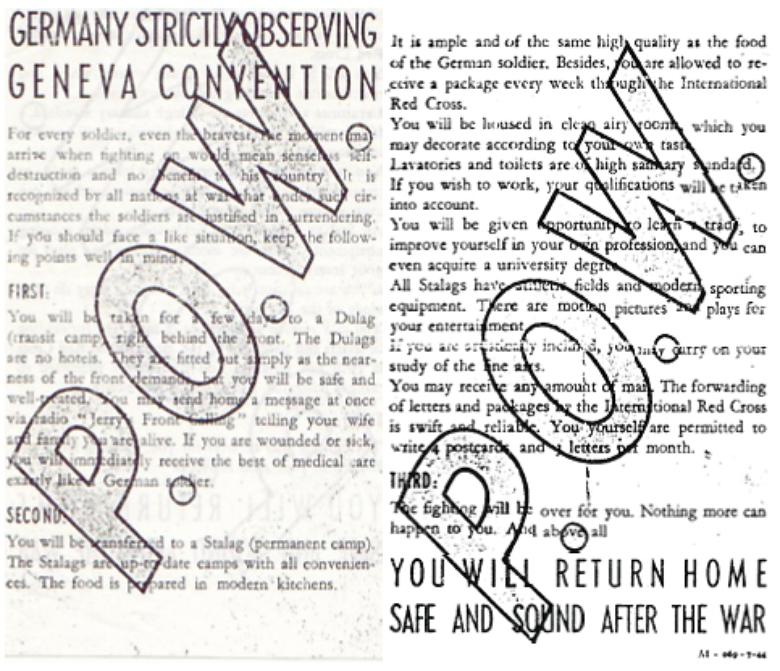

German Propaganda

show infoDescription:

German propaganda designed to encourage surrender

Credit:

Robert Owens

Tags:

The 51st Highland Division was under the command of the French Army Corps. We attacked the Germans at the Somme, but after delaying the German advance for two days,were forced to retreat, along with the French forces, to the Normandy coast near St Valéry-en-Caux. A defensive line was set up in the hope that ships would be sent to rescue us. This was a forlorn hope. We were attacked by a huge force of tanks (later estimates put the figure at around one hundred), and bombed by Stukas.

Pinning the Highland Division and the four dispirited and fragmented French divisions of XI Corps into a bridgehead just seven miles wide and five miles deep by noon on 11th June were five near full strength German divisions and one motorised brigade. They included the 2nd Motorised and 5th Panzer Divisions, advancing from the south and southeast respectively, and the 7th Panzer Division, moving in for the kill from the west.

…At midday, with about two hundred tanks of the 25th Panzer Regiment leading, closely followed by the motorised infantry of the 6th Rifle Regiment, the 7th Panzer Division rumbled towards St. Valéry, just six miles away. Directly in its path wee the hastily prepared defensive positions occupied by the 2nd Seaforths, the company of 7th Norfolks, and the 1st Gordons…

At 11am Major Grant [of the 2nd Seaforths] decided to go in person to request some artillery support. He was told that a battery of the 1st Royal Horse Artillery was being sent, and that some guns of the 51st Anti-Tank Regiment would also move up. By 1.30pm …Second Lieutenant Burnett had completed a recce to site his guns… In his memoirs, Rommel talks of “heavy artillery and anti-tank gunfire” greeting his tanks, forcing them to bear off to the southeast…But it was like trying to hold the tide back with a sand wall.

(Ref. Saul David: “Churchill's Sacrifice of the Highland Division”. )

We retreated to the beaches, but found that the Germans had the high ground. They dominated the beach with heavy machine guns and mortars, and used them to devastating effect. We had nowhere to go. The French raised the white flag of surrender. This was resisted by the British troops; however soon afterwards, we received a message from the British commander General Victor Fortune ordering us to lay down our arms “to save useless loss of life”.