Henry Owens' March into Captivity

Summer 1940

“Dear Henry,

I am so glad to hear that you are alright and are being treated the same… I know just how you feel about it all, but we all have to do those things in life we do not like, and to leave ones home for so long is about the worst of them all, but like all bad things, it will come to an end, and then you can tell us all about it, and what a big and great chap you will be to all at home. “

I was taken prisoner with most of my Division (51st Highland) on 12th June 1940, by Rommel, later known as the Desert Fox. We were force-marched through France; in fact it would be fairer to say they made us run through France, as it was obvious that they feared that another landing of British troops might take place to rescue us. We were beaten with rifle butts, kicked and abused to keep us moving, anyone falling out of the column ran the risk of being shot (as many were), although in some instances, men were picked up by motorcyclists and taken away, as happened to my fitter sergeant Ian Macmillan. Much later, we found out he had died.

I remember that we were held overnight at Arras racecourse, British and French together, when it was announced that an Armistice had been signed. The French were delighted, as they thought that they would now go home. Friction broke out between the British and French, which seemed to be encouraged by the German guards. The next day the French were still marched out with us, much to their distaste.

The march got worse, there was very little food. A moldy loaf of black bread between six men, and a meagre ration of ersatz coffee for those who had a tin or a dixie, was supplied at Arras, after we had queued for about five hours. The coffee was soon lost, as we had to run, being helped on our way by kicks and oaths.

The weather was extremely hot. We marched on without any water, which was worse than the lack of food, and out of desperation, we drank anything from pools made by rain, or out of cattle troughs. Consequently we suffered from stomach ailments and dysentery. I must mention that the French women were marvellous. They would leave buckets of water and containers of boiled potatoes at the roadside, which invariably were kicked over by our guards. These ladies took considerable risks, and were often roughed up. Their efforts helped us to survive and we owe them our grateful thanks.

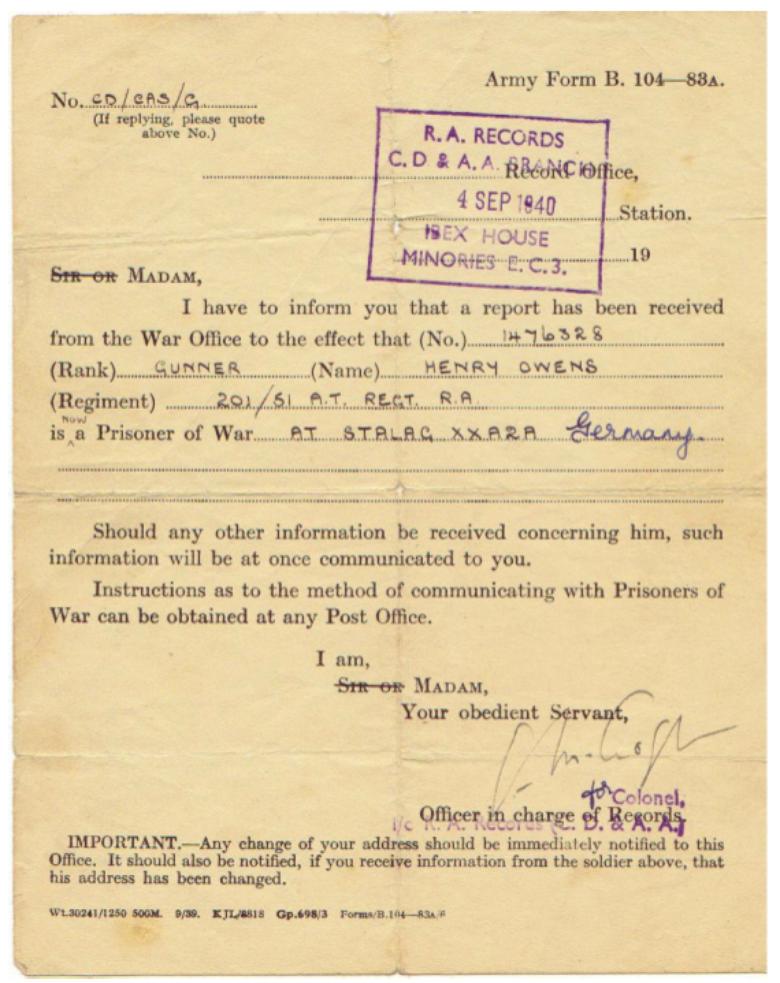

Official notification of POW

show infoDescription:

This is a scan of the letter Henry Owens' Mother received officially notifying her of her son's (Henry Owens) capture and status as a POW. Dated 4th September 1940.

Credit:

Thanks to Robert Owens (son of Henry Owens)

Tags:

One lady pushed a napkin into my hand. Inside was a note telling of the news from the BBC, such as reports of the bombing of the Italian ports, and such like. The note also asked me to write the name and address of my next of kin so that they could be informed that I was a prisoner. I was to hand the note, with the address, to another lady, about a kilometer further on; this lady would be holding a napkin for identification.

I wrote down my mother's name and address, and duly passed it on to the lady with the napkin, although I had little hope my mother would receive it. As it turned out, this was the first news my mother had that I was alive; in fact she had to inform Army Records! The Comité de Béthune Red Cross Women‟s Section, sent the note, and I am eternally grateful to them. They added the word “prisoner” to the note, and forwarded it to my mother.st Anti-Tank Regiment, 201 Battery, 51st Division based at Bordon in Hampshire, as they were short of gun fitters.

As dysentery took hold, we had to stop more and more to relieve ourselves. We used to dash into the fields and take our trousers down, until the Germans started to use us as target practice (a soldier next to me was shot), and we all raced out of the field trying to pull our trousers up. After that, we soiled our trousers rather than go into the fields.

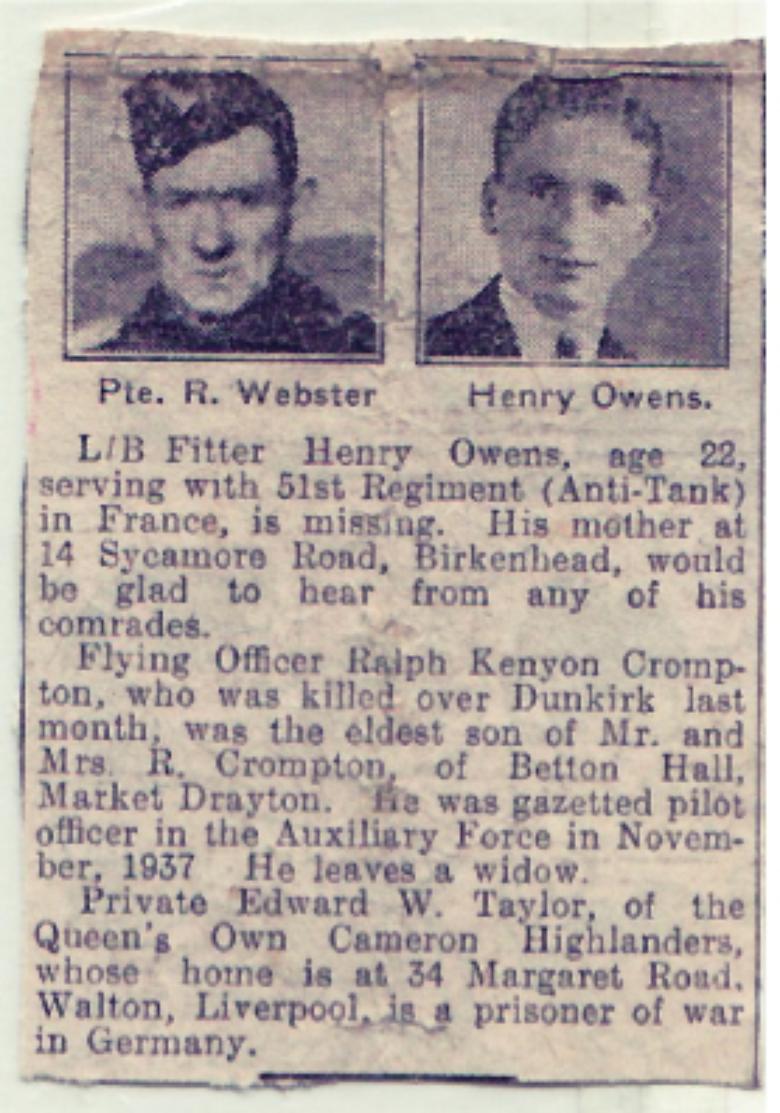

Henry Owens - Newspaper Clipping

show infoDescription:

Newspaper Clipping on Henry Owens from his home town reporting him as 'missing'.

Credit:

Thanks to Robert Owens (son of Henry Owens)

Tags:

Eventually, after marching through France and Belgium, we were bundled, or should I say stacked, into open railway trucks in Holland, and taken on a journey to the Rhine at Wesel. There we were given a loaf of mouldy black bread, and pushed down a ladder into the bowels of a filthy coal barge. It was pitch dark and airless, and was more terrifying than the march. The stench was awful.

When the barge got under way, we were allowed to take turns to come on deck, and a makeshift toilet was rigged up, with just a pole to hang on to whilst you relieved yourself. Needless to say, the death toll started to mount. We endured this for about three days until we reached Germany proper, after a short rail journey to Dortmund, where the Nazi flags were flying to celebrate their great victory.

We were shoved into cattle trucks, which bore a notice saying eight horses or forty men. Between sixty and seventy of us were loaded, and the doors were locked. We only had a little grill at the top to let the air in. There was not enough room on the floor to sit down, so those who were fittest stood. We had no food or water, no toilet facilities; the stench once again was awful, as there was no means of getting rid of the human waste. We used our dixies (if we had any) to urinate in, and then tried to pour it out of the grill. Those who had no dixie either borrowed one, or used their boots for the same purpose.

This journey was simply horrific, and I do not use the word lightly. It lasted between three and four days, until we eventually arrived at our destination - Torun (Thorn) in Poland, and we marched, in a pitiful condition, to a balloon hangar for processing, and to be photographed and provided with a new identity tag. My number was 14704. I was issued with a thin Polish uniform to replace my tattered British one, which stank after the ordeal that we had endured.