Pte. MacPherson Diary Extract, Somme, July 1916

Attack on High Wood

The following extract is from Pte. MacPherson's Diary of Active Service. MacPherson, 9th Royal Scots (154 Brigade), wrote this diary whilst recovering in hospital during the summer of 1917 from notes in his pocket diary. Please note - MacPherson's words have been unedited and describe scenes that some readers may find distressing.

The Attack on High Wood

"21st July 1916

Next day all was bustle and preparation for our attack. Men were detailed as runners and scouts, reserve Lewis Gunners were chosen and orders as to equipment issued. Our packs had to be named and numbered and stored and only the haversack containing emergency rations, shaving and washing kit, waterproof sheet and mess tin was to be carried. Many, imagining the attack would only last a few hours, would have left sheet and mess tin behind, but luckily orders compelled us to take these necessaries. Some changed into their clean spare shirts for some strange reason of the own. Water bottles had to be filled and rifles cleaned.

While this was going on we could see from the sloping expanse we were camped on a wide stretch of level ground round Meaulte and Fricourt villages. This great plain was absolutely devoid of grass and was covered by great “dumps” of shells, bombs and ammunition; transport lines with horses tethered to ropes beside rows of wagons; and tents or bivouacs. Across it tramped battalion after battalion (all remnants of battalions rather) of infantry, every second or third man carrying a polished German dress helmet as a trophy, or long lines of India Lancers whose camp lay beyond the railway in readiness for the “breakthrough”.

Overhead hung the huge bulk of Observation Balloons, swaying in and warm breeze, and whichever way one looked these ominous shapes dotted the sky. Aeroplanes buzzed up in the air while on the far horizon, behind which laid mysterious battlefield, puffs of smoke denoted shell bursts. In the fine summer sun the scene looked cheerful and glorious to us as we look on it from our lines. As the afternoon wore on we prepared to move. The Companies and Platoons fell in and were inspected by their officers. Ours told us in a short speech not bother to take prisoners, a rash order which no one got the chance to carry out. Then we moved off and marched towards the firing line.

8-inch Howitzers, Fricourt-Mametz Valley

show infoDescription:

8-inch Howitzers of 39th Siege Battery in Fricourt-Mametz Valley, August 1916.

Copyright:

IWM Q5817

Tags:

As we plodded up the dusty road to Fricourt we passed a battery of howitzers firing and I, for the first time, noticed that the shell is visible as a black blur when it leaves the gun’s mouth. Next we passed the old front line trenches now all crumbling and ruined by Bombardment with torn and twisted barbed wire entanglements still standing between. Of Fricourt villagenothing remained but heaps of ruined bricks and rubble. We were now in what had been since 1914 German territory and looked around us with strange feelings. Everywhere along the roadside were transport camps, horselines, heavy batteries, R.E. and Ammunition Dumps, Watering places, etc. and the occupants would crowd to the road to see us pass. How many battalions of infantry had they seen marching sturdily “up the line” full of confidence only to return in a few days, reduced in numbers, exhausted, weary and longing for a rest from the terrible trials they had come through.

We next passed through the ruined village of Mametz, where lay the 6th Argylls and Forth Garrison Artillery. As we left Mametz we got a whiff of tear shell gas still lingering after German bombardment, which made our eyes sore and watery. Our road now dipped down into a valley and approached Mametz wood which we passed on our left. On the hillside to our right we passed a large wooden cross grey painted erected by the Germans on the grave of some of their dead with withered flowers still lying on the ground beneath. German dugouts showed their dark entrances in the cuttings through which the road past, and a single line railway built by the enemy with its rails in many places shattered and bent by explosions testify to the industry of the invaders.

Ruined Mametz, July 1916

show infoDescription:

Mametz village in ruin. Taken 4th July after its capture by the 7th Division on 1st July 1916 during the Battle of Albert.

Copyright:

IWM Q773

Tags:

Darkness was falling fast as we reached the end of Mametz wood and the ruins of Bazentin le Petit so we halted under cover of the steep sides of the valley here forming a sort of quarry. Hitherto are advance had been uneventful. Now the wailing roar of approaching shells was heard and with resounding crashes these messengers of death burst in the shattered houses of the adjacent village. This seemed to be the signal for both sides to liven up.

Away in front the sky was illuminated by the glare of the Verey lights or starshells, while the artillery began to open up. The order came to advance and we left our shelter to move up a narrow gully, fringed on the right by a shattered wood (of Bazentin le Grand). Instantly we plunged into a hail of shells. Extended in a long twisting single file we rushed on at top speed, now stumbling up a trench, now darting across the open, into shell holes, over shattered trees, always nearing the weird glare of the flares in the front. Meanwhile all around fell a hail of shells.

The air was full of the roar of their approach, the drawn out shattering detonations of their explosions and the whine or whistle of splinters, while the fumes of cordite were carried on the evening breeze and the darkness was illuminated by the flash of the bursting shells. Expecting every minute to be blown to atoms, with shells bursting all round and on every side, we continued our rapid advance and at length with a sigh of heartfelt relief found ourselves beyond the barrage near the comparative safety of our fire trench. This was a shallow ditch at the foot of the banking of a sunken road broken down by shell fire in which crouched the survivors of the preceding Division whom we were to relieve. We filed along the trench exchanging whispered questions and answers from which we discovered our predecessors were Worcesters and that they had made an unsuccessful attempt to occupy High Wood and had suffered terrible losses. Then they disappeared in the darkness and left us to settle down in our new position.

The cause of the artillery liveliness was evidently an attack on our right where the fire of rifles and cannon was continuous, and where flares and rockets shot up incessantly. Now our sector was quiet and after posting sentries we set about deepening our trench best we could. Little could be done however till daylight and when this came at last we could see our surroundings clearly.

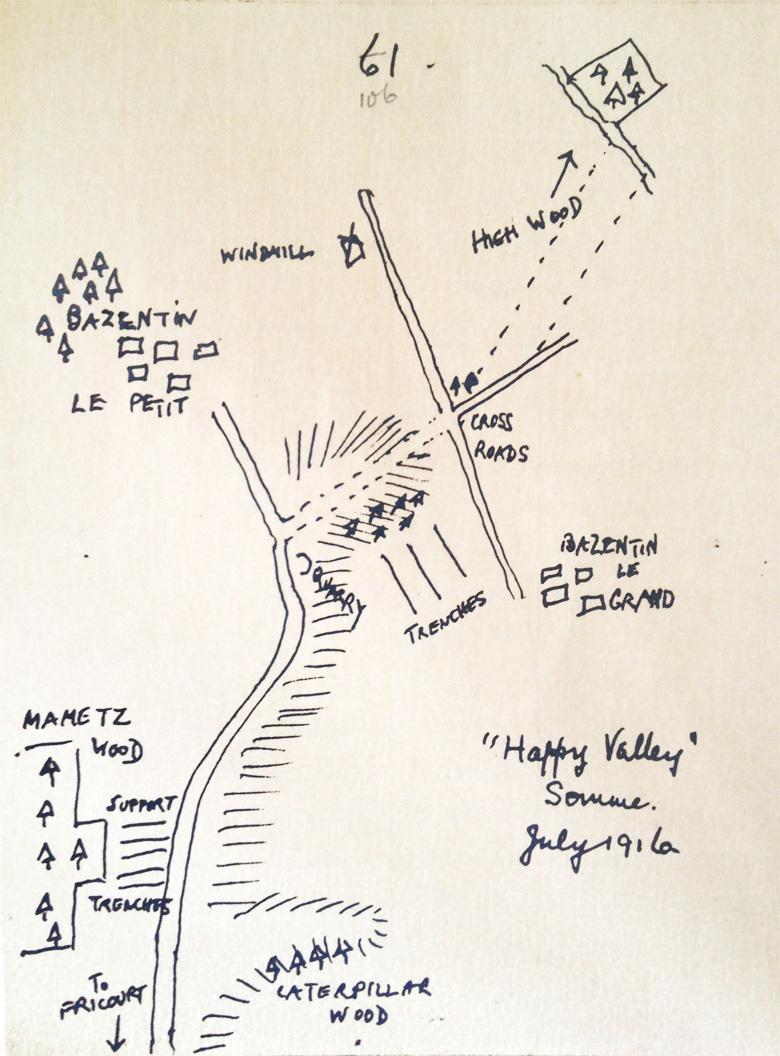

MacPherson Sketch "Happy Valley"

show infoDescription:

Sketch map by Pte. MacPherson, 9th Royal Scots. Caption reads "Happy Valley", Somme, July 1916. Sketch illustrates trench positions between Mametz Wood and High Wood around Bazentin. Sketch forms part of MacPherson's diary of Active Service.

Credit:

Pte. MacPherson

High Resolution Image:

Tags:

The road on which our trench ran was bounded on one side, that nearest the enemy, by a steep bank which formed a fine natural parapet. Below this ran the trench, not much over knee deep and with no fire step to speak of. On looking over the bank we saw only our own barbed wire, a straggling irregular belt, and the ground in front all torn with shells, grassless and treeless, which rose gradually and shut out any view of the enemy who lay beyond the immediate rise. Looking backwards over the road the ground similar in its lack of grass and trees, pitted with shell holes, and with here and there a huddled, stiff corpse, sloped down to the wood of Mametz and the ruined village of Bazentin le Petit. On our right the ground rose to the village of Bazentin le Grand, where the most conspicuous ruin was that of a factory with its boilers and tubes twisted in shattered by shell fire. On our left, and in the rear of the road, was a tall square windmill tower, half ruined, from which a brave French artillery observer used to watch for targets in the enemy’s lines. Such were the surroundings our position on 22nd of July, 1916.

High wood lay about a mile in front but out of sight.

That day was spent in deepening the trench, in digging “funk” holes or small caves in the parapet and otherwise preparing for the “strafe” to come. Owing to the rise of ground in front which slightly screened us from the enemy, and also the steep bank above the road we could risk moving about in the latter now and again. In the evening some of us were detailed to bring up the rations. This necessitated a journey down to the valley of Mametz wood via the gully up which we had come, and gave us an opportunity of viewing by daylight what we had passed the night before in darkness. In the strong sunshine of the July day the horrors of the path were manifest and we walked in some places looking neither to right or left the fear of what we might see.

The whole surface of the earth in the gully was torn up and pitted with shellholes, littered with broken or discarded rifles, equipment, bombs and helmets. Under the cover of the wooded bank was the site of the German battery still marked by several heavy shells abandoned by the gunners in their retreat and by numerous long basketwork cases used for carrying such. The earth wreaked of explosives, and this odour was reinforced by that of some dead horses lying horribly distended to unnatural size. Under cover of the roadside were collected the corpses of some of our English troops who have met their death in the fatal gully. One lay on a stretcher stiffly stretched out and covered by a waterproof sheet, as he had perhaps been left by the stretcher bearers days before. At the crossroads on the right of our trench stood two battered German Field Guns. Chalked on their shields was the inscription “Taken by the –th Manchesters” who I believe took the guns in a bayonet charge - rather a singular occurrence.

Craters, Mametz, July 1916

show infoDescription:

Shell craters close to Mametz Wood. July 1916

Copyright:

IWM Q116

Tags:

Luckily for us things were quite quiet when we went down the gully that afternoon. The ration limber was waiting for us at the Quarry and as you can expect there was no delay on either on our part of that of the storemen. We hoisted our loads and made off up the trench as quick as possible, arriving there without any misfortune. At night the rations were issued and after tea we had left for the next day a bit of ham, a slice of bread, some tea and sugar. This we stowed in our haversacks to keep for future use. Before darkness fell everyone prepared for the attack. We bombers carried besides the full battle order (rifle, bayonet, 120 rounds of ammunition, haversack on back with waterproof sheet, messtin, cleaning kit, rations, entrenching tool, steel helmet) a large bag like horse’s nosebag containing bombs. So many had wire cutters fastened to their rifles. These resembled shears in shape and worked similarly on being pressed on the wire.

After seeing our equipment was complete all we could do was wait for events. So in our funk holes or on the firestep we waited for the arrival of “B” and “C” companies (the first wave of the attack) who were lying in trenches beside the quarry and were to come up and lead the way.

Darkness fell and the artillery began to liven up. Rumours about the attack were widespread amongst us. It was said that 15 platoon of “D” Company were to reconnoitre the Wood first and that our advance was to be over a considerable distance.

The artillery fire became nearer. German shells came roaring through the darkness, whistled and shrieked overhead, and burst behind or in front of our trench. All were crouched under the parapet except the sentries who peered over the top into the darkness watching for any movement in front. At first with every whistle of a shell passing close overhead the sentry would duck - a useless but instinctive act, useless because if he could hear the shell it must already be passed him.

At last the sound of movement came up the road from the right and soon a long line of dark figures filed up behind our trench and halted there. This was the first line of the attacking force, “B” and “C” Companies, arrived in position at last. Whispered conversations between them and our companies in the trench revealed the fact that they knew is little about where they were to advance as we did. 15 Platoon of our Company was called out to carry out the reconnaissance and we began to close down to the right to join 16 Platoon but 15 Platoon was then sent back to take part in the attack with the rest of the Company.

Meanwhile “B” and “C” Companies lay down the road behind us and the artillery opened up on both sides with terrific fury. Huddled at the foot of our trench, crouching against the parapet or squatting on the firestep (where there was such a thing) we awaited the signal to advance. The roar of approaching shells, the whistle of those passing close overhead, the deafening rumbling crash of exploding H.E., the metallic “twanging” detonation of shrapnel, the whine of shell fragments, the cracking and whistling of machine gun bullets all combined to produce the full concert of modern war.

The air was heavy with the acrid fumes of cordite; showers of earth and stones from the explosions of the H.E. fell in the trench, confusion reigned supreme. It was impossible to hear messages even when shouted at three feet distance. Now and again, in the glare of bursting shrapnel overhead or H.E. on the ground we could catch sight of our comrades lying on the road behind and crouching in the narrow trench.

Now the German shells began to catch our position. The ominous message “Stretcher bearers” was passed the man to man, and these men, whose job is perhaps the most final of all in an attack, were soon busily engaged bandaging and carrying the wounded.

As I sat on the firestep, close against the traverse, I heard the menacing roar of the German H.E. shell approaching. In an instant I realised it was going to be a near one and crouched close to the parapet for safety. A whistle close overhead near the edge of the bank, a blinding flash, a deafening crash, a blast of hot air and cordite students, a shower of earth and stones, I was left bewildered with the shock and uncertain if I was alive or dead. The shell had landed right on the road behind me full in the centre of the “B” Company men lying there and the groans and cries the wounded and dying woke me to action.

Those who could whirled headlong into the trench and those of us who were at hand were busy bandaging. We forgot for a time the bombardment in our haste to attend to the wounded. The Sergeant of the stricken platoon (No.6) who I had known at Peebles came in beside me struck in the foot, but refused my offer to dress him till his men were all attended to. Together we went on to the road to bring in three who were still lying there, one of whom was groaning and therefore still alive. We took him first, the Sergeant going to his head while I seized his feet. The leg I touch first was smashed to a pulp for when I raised his foot the leg bent like a truss of straw. We decided we could not move him ourselves. The stretcher bearers were at hand and took charge of him and carried him off. Next we prepared to raise the other two. The flash of the bursting shrapnel shell lit up their bodies and showed their heads horribly crushed. We realise they were both dead and return to the trench. The Sergeant went off down the road to risk of the shells and shrapnel on his road to the hospital.

Meantime there were still wounded to be attended to. One man (of the 8th R.S. attached to us) was covered with blood all over his tunic and a helpless against the parapet. We opened his shirt but could find no wound on the body and finally discovered he had been hit on the jaw and the blood to flow down over his jacket.

At this point the order came down for us to fixed bayonets for evidently “B” and “C” Companies had gone “over the top” just after the shell struck No.6 platoon. We hastened to our posts and prepared to follow but after waiting some time the order came to “Stand down”. Our attack was cancelled and I think all of us were relieved at the news.

The artillery fire began to slacken as the night wore on and the survivors of “B” and “C” began to strangle in over the parapet. The Battalion Bombers had been wiped out by a shell so two of us were sent up to take their place. As we made our way up the trench we had to step over bodies in our path but we were now so accustomed to such sights they did not affect us at all.

Dawn was now breaking and as the light strengthen we could see stragglers of the attacking Companies coming in through the wrecked barbed wire and across the waste land now pitted with shells and strewn with bodies. The artillery now had slackened off completely and we could breathe freely once more. Beside us was a Sergeant of the West Kents who had lost his Regiment was sheltering in our trench. He was a complete nervous wreck, trembling all over and would not take the advice given to him to clear out to the dressing station. At last he plucked up courage and made off. Those of our men who had hung on in the trench, though wounded, rather than risk the passage of the deadly galley now began to make their way down the road for hospital and “Blighty”.

The survivors of the two attacking companies were now marched off to their old position behind the Gully and we were left to “clean up” our trench. The dead had to be stripped of valuables (pocket books, rings, watches, etc.) kept for sending home later, and then were carried in waterproof sheets across the road, placed in shell holes and covered with loose earth. This makeshift burial performed, rude crosses made of pieces of ration boxes with the name, number and regiment of the dead soldier, were erected to mark the place. Though the burial was carried out without any service or spoken prayer, nevertheless the uncertainty of life will be more strongly felt in such circumstances and with all the pomp and ritual of Church Service. When the burial party know they may any minute follow the path of their comrade they are burying, there must be an earnestness in their attentions, however rude makeshift they may be, often lacking in such ceremonies in normal times."

Personal account from Pte. MacPherson, 9th Royal Scots, 154 Brigade, of the Battle of Arras betweem 15th - 24th April 1917.

Division History References :

During the Battle of the Somme, High wood had been taken by 7th Dragoon Guards and Deccan Horse but part had subsequently been retaken by the Germans. The division was ordered into the line on 21 July that evening. With less than twenty four hours to prepare, on 22 July 1916 the Division was ordered to attack High Wood...