Pte. MacPherson Account Battle of Arras

15th to 24th April 1917

The following personal account is taken from the diary of Private A. F. MacPherson, 9th Royal Scots, 154 Brigade, written during the summer of 1917 whilst in hospital recovering from his injuries received during the Battle of Arras.

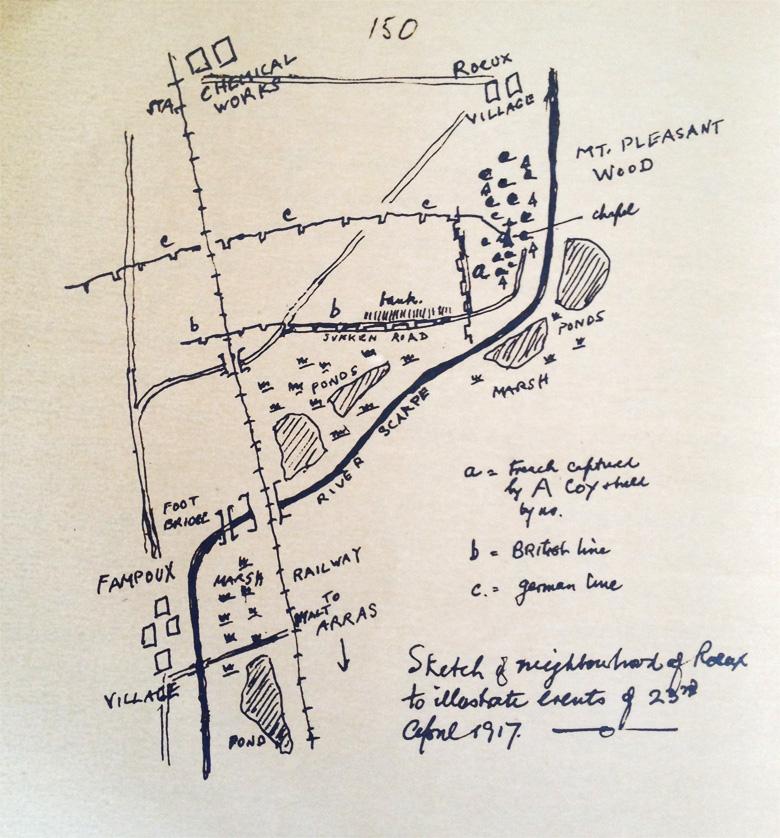

Sketch Map Fampoux to Roeux

show infoDescription:

Sketch map made by Pte. MacPherson, 9th Royal Scots, illustrating German and Allied positions around Fampoux and Roeux Villages along the River Scarpe during late April 1917. Sketch comes from MacPherson's diary of his Active Service.

Credit:

Pte. MacPherson

High Resolution Image:

Tags:

"On the night of 15/16 April 1917 the Division had relieved the Light Division East of Fampoux.

The Argylls arrived shortly after and took over with the usual whispered injunctions and information. The artillery officer came to find the position of the chapel in the wood in order to knock out the machine-gun post there. We pointed out the obnoxious edifice as well as we could and he departed to his guns in the rear to prepare for tomorrow's "strafe".

The Argylls seem very confident of success and assured us that next day they would chase Germans as far as required. We now left our trench again and the entire Battalion was assembled on the sunken road. As the Argylls occupied the main trench also we were told to dig in behind it using picks and shovels most of us carried. Rations had to be brought up for the next day so several men were taken off on this duty. The rest of us began to dig ourselves little slots in the ground to afford at least some shelter and, exhausted after this toil, lay down in them and dozed off. We were sharply awakened by Sergeants and Officers and the fatal “five minutes to go” passed along. We rubbed the sleep from our eyes and seized our weapons. I saw that the magazine on the gun was full and in order and laid aside its waterproof sheet. As my rifle was a handicap in carrying the Lewis gun, I laid it aside at this stage as an encumbrance.

A gun boomed behind and next instant the whole sky behind was lit up with flame as our artillery opened their barrage on the German trench in front. It was impossible to hear even a shout above the noise, the roaring whistling of our shells approaching and whizzing with a menacing rush just over our heads, the long sustained crashing detonations, the whining of the splinters or shrapnel bullets combined to form a terrible tornado of destruction.

The German trench was shrouded in a dense cloud of smoke broken by lurid flashes of flame where shells were bursting and from which rose in clusters the enemy’s Verey lights anxiously shedding light on No-Man's-Land. Overhead the air was rent by the bursting shrapnel, the fumes of the explosions drifting slowly along, flashes lighting up the faces of the men crouching in the trenches and the peculiar metallic desolation of shells merged in united war of the bombardment.

In addition to the artillery barrage, the curtain of machine-gun fire was laid on the German supports and sustained crackling and whining of the bullets as they pass over overhead or to the side of us added to the din. The rattle of the Machine Guns, both British and German, swelled the tumult and now hostile shells were bursting in our trench and in the river, inaudible in the general noise but nonetheless destructive.

The Argylls disappeared “over the top”. We clambered into the empty trench and fixed bayonets. The Platoon Sergeant was throwing to us a cake of chocolate and a tin of sausages to be shared between two. Most of us ate the chocolate at once to make sure of it and stuffed the tin in one of the pockets of our greatcoats for future use. All the time the tremendous bombardment was raging. I scrambled up the bank and looked over. In front lay No-Man's-Land, empty pitted with shell holes and in front again the cloud of smoke still drifting over the German lines.

There was not much feeling of fear at such a time. Excitement, a feeling that now we would get it over and be done with suspense, combined to keep us nerve up to the pitch required. The feeling too of helplessness to avoid anything, a sort of fatalistic knowledge that we could do nothing to save ourselves helped to keep us calm. It all seemed more like a dream than reality. Also exhaustion and hunger and want of sleep keep one's desire to avoid death in check.

Dawn was breaking. The officers scrambled up the bank and with a shout inaudible in the tumult and a wave of the arm led us over the top. [4.45 a.m. per Divisional History] In a long straggling line we rushed forward over the shell torn ground plunging into shell-holes, conscious of the need for haste and feeling as though our feet were weighted with lead and as if we were crawling along instead of running (which of course we were). All round whistled the machine gun bullets lashing the ground as if in a spray but no one heeded them. The German barbed wire, battered and torn by shellfire, was soon passed through, though it always is as well to pick one's steps and choose an easy path in getting through that fatal barrier. Many soldiers caught on its barbs had been delayed long enough to let the Machine Guns riddle him with bullets or the sniper mark him as his prey.

We leapt into the first trench (now empty) scrambled up the other slope and ran on. Here we halted for a few minutes and took cover in the numerous shell holes while he had time to look round. In front of ground seemed to rise to a crest crowned with a clump of trees, and then dipped once more. All the shrouded in mist but the dim light of dawn showed numerous figures running back and forward it. Were these Germans or Argylls? Most decided to former and opened fire and we did so with the Gun.

Lamont, Orr and I were together on the same hole with two men of 15 Platoon. The Sergeant Major on our right signalled to us to come forward with a wave his arm and I got out of the shell hole and on my hands and knees began to crawl to the next one dragging the Gun. Before I reached it I received a terrific blow on the left side which took my breath away and I realise I was hit. I plunged into the hole and lay down my back keeping well undercover. Every breath caused me pain and on looking for the wound I found a hole as big as my hand in my greatcoat on my left side below the breast.

From the position, I at once concluded the worst and the pain of breathing made me think my lungs were damaged. However as nothing further happened I took heart unbuckled my equipment, took out my field dressing, applied it on the wound which was foul with earth and fasten my tunic up to keep it in place. Meantime our fellows and the Germans were firing at each other over my head, bullets were striking all round and occasional enemy shells bursting near.

The bombardment still raged. Orr came crawling over to me to find out what was wrong - a very risky thing to do. He saw my dressing was right then took the gun and sought shelter again. Soon after they advanced and rushed forward with a cheer and the sound of battle began to recede. German prisoners, with hands aloft, came rushing past in groups and messengers ran up and down from the front to rear. Lamont, who had been bandaging a Sergeant struck with an alleged explosive bullet, now rushed forward speaking to me as he passed.

Things became quieter. The sun now shone brightly and except for an occasional shell, the fighting seemed to be considerably in advance of my position. I could see nothing, however, of my surroundings over the rim of the shell hole. A German Stretcher Bearer, evidently a prisoner, had been going from shell hole to shell hole at considerable risk dressing the wounded now came across to me, but I pointed to my dressing so he ran on to attended someone else. One of our officer’s servants carrying a bag rations came in beside me left it in my charge before going on.

One or two of our men and a stretcher bearer now came with a stretcher, got me on it and carried me into the German trench where they left me to attend to others. There was a great shortage of bearers and hardly any men could be taken down to the rear. The pain in my side prevented me from rising and, imagining I was worse wounded than I latterly turned out to be, I lay still when I might, though much pain and risk perhaps, have managed to struggle down to the Dressing Station with assistance.

Some Argylls in the trench covered me with a German blanket and as the sun shone I was quite warm. Here I lay all day, appealing to every bearer who passed to get me away but with no success. Either they had their own men to look after first or had a case just further up the trench and would be back soon. They never came back.

Several of our chaps slightly wounded passed down from line, also a Corporal of our company looking for stretcher bearers who told me of some other casualties. We had evidently lost heavily. The Brigadier and his Staff Captain, Captain Paulin in of our Battalion, passed along and the latter spoke to me and assured me I would be lifted soon but the shortage of bearers was delaying prompt attention to the wounded. Later a lot of Seaforths passed by returning from the front or going to another point. All this time shells were whizzing past some bursting very near, and it is ridiculous to think I used them to cower under the blanket drawing tight as if that would protect me. Stupidly I had left my Gas helmet in the Shell hole so I was powerless against gas. Luckily it did not come into use that day. With my steel helmet well over my face and my head whenever a shell came near, I hoped to avoid further injury and though several times earth fell on me from shell bursts, nothing more serious landed there.

So the long day dragged on. A Gordon wounded in the leg crawled down the trench and stayed beside me, and we shared the blanket as well as we could.

Night fell and still no bearers though we shouted for them now and then. At last movement began in the trench and a Battalion of English troops, the Northumberland Fusiliers, (I think probably the 26th or 27th Battalion which, according to the History now came up as a reserve) filed in. We had to call out continually to warn the men not to trample on us as we lay on their path. Later some of our Division came down. The Northumberlands finally occupy the trench and began digging.

As can be imagined, our presence was a hindrance as we blocked the trench up so they decided to remove us and procured a stretcher. I was lifted first and then the journey to the Dressing Station began. Four men carried it shoulder high with two as reliefs and it was a difficult job getting down the trench and round the corners. I must have been no lightweight but they stuck it nobly and finally reached the sunken road. Here shells were landing too near to be pleasant and we had to shelter under the bank often for safety but at last we reached the dugout used as Aid Post and found there a lot of other cases waiting bearers. These (R.A.M.C) arrived from the Dressing Station but my bearers were made to continue their service much to their indignation.

Dressing Dugout, Arras

show infoDescription:

Advance dressing station within a dugout, close to a battery of 18-pounder field guns. The village in the distance is Monchy-le-Preux, east of Arras, under fire from German positions. The photo is dated 24th April 1917 and is from the Imperial War Museum collection.

Copyright:

IMW Q6293

Tags:

We went on across country, as far as I can remember, down the railway for a little way and over a bridge and last reached a dugout used as Dressing Station. Here a new dressing was applied, I was put on a trolley and pushed down to Arras where the Field Ambulance was. First of all we were taken into a cellar in an isolated house and examined by a doctor. A fresh dressing was put on my wound and I was told not to worry. Men hit in the body are not supposed to have a drink but I got a little hot tea. A number of us were then placed on a trolley again and taken down the railway to the Field Ambulance itself, in a factory building. Here we were inoculated against Tetanus and then placed on electric trolleys for transit to the Casualty Clearing station at Duisans.

It was now daylight (April 24th) and we travelled through Arras and finally reached Duisans. Here we lay sometime in a large ward. The doctors examined us again, probed at my wound and put on another clean dressing. It was very warm and I slept a little. The next move was onto the hospital train for the ase.”

Private MacPherson landed in Dover on 5 May 1917 and did not return to active service.

Division History References :

The 51st Highland Division in the Battle of Arras during the First World War, April 1917